5.3High Level Framework for Automata

For the most part, we have described finite-state and pushdown automata using state transition diagrams. While state transition diagrams are great for analyzing automata, in my opinion, they are not as helpful that for designing automata (especially for beginners) and the notation for state transitions can be quite cryptic for pushdown automata.

We are now going to see a more explicit way of describing automata that is more akin to programming.[1] The hope is that it makes automata clearer by allowing students to draw on their previous programming experience. Along the way, we will also discuss how to analyze the correctness of an automata.

5.3.1Deterministic Finite Automata¶

Schematic diagram of a finite automata. The finite control box represents the various states and state transitions of the finite automata.

We model a DFA as a program whose input is presented on a tape. In particular, the tape is subdivided into tape cells with one cell per input sybmol. The program also controls a “tape head”: it can read the input symbol currently under the tape head and move the tape head to the right by one cell.

The program consists of code blocks. A code block starts with its

label followed by exactly 3 If statements. The block labeled Start

is special: this is where execution starts.

The 3 If statements correspond to the cases that the input symbol

under tape head is equal to ‘1’, ‘0’, or and the case that there is no

more input. Each of the first two If cases has exactly two statements:

Move Right which moves the tape head to the right by one cell, and a

Goto <label> statement which causes the execution to jump to the start

of the corresponding block. The third If case (when the input has

ended) has exactly one statement and is either Accept or Reject.

The equivalence between the usual definition of finite automata and the above is straightforward:

blocks correspond to states

the first two

Ifstatements of a block correspond to the transitions out of the corresponding statethe last correspond to whether the state is accepting or not

5.3.2Best Practices for Designing DFA¶

The crux in designing a DFA is figuring out how to encode information about the string we have seen so far using a finite number of blocks/states.

Consider the task of determining whether a string has an odd number of

1s. It suffices to keep track of whether the number of 1s we have seen

so far is odd or even. Thus, Figure 2 has blocks OddOnes and

EvenOnes. The idea is that the following holds true throughout the

execution of the program[2]:

it enters the

OddOnesblock if and only if the number of 1s seen so far is oddit enters either the

Startor theEvenOnesblock if and only if the number of 1s seen so far is even.

It is not too hard to convince oneself that they hold true because[3]:

At the start, we go to the

EvenOnesblock if the first input symbol is 0 and theOddOnesblock if it is 1Suppose we have already seen an even number of ones. That means we are in the

EvenOnesblock. If the next input symbol is 0, we go to theEvenOnesblock, and if it is 1, we go to theOddOnesblockSuppose we have already seen an odd number of ones. That means we are in the

OddOnesblock. If the next input symbol is 0, we go to theOddOnesblock, and if it is 1, we go to theEvenOnesblock

5.3.3Pushdown Automata (DPDA)¶

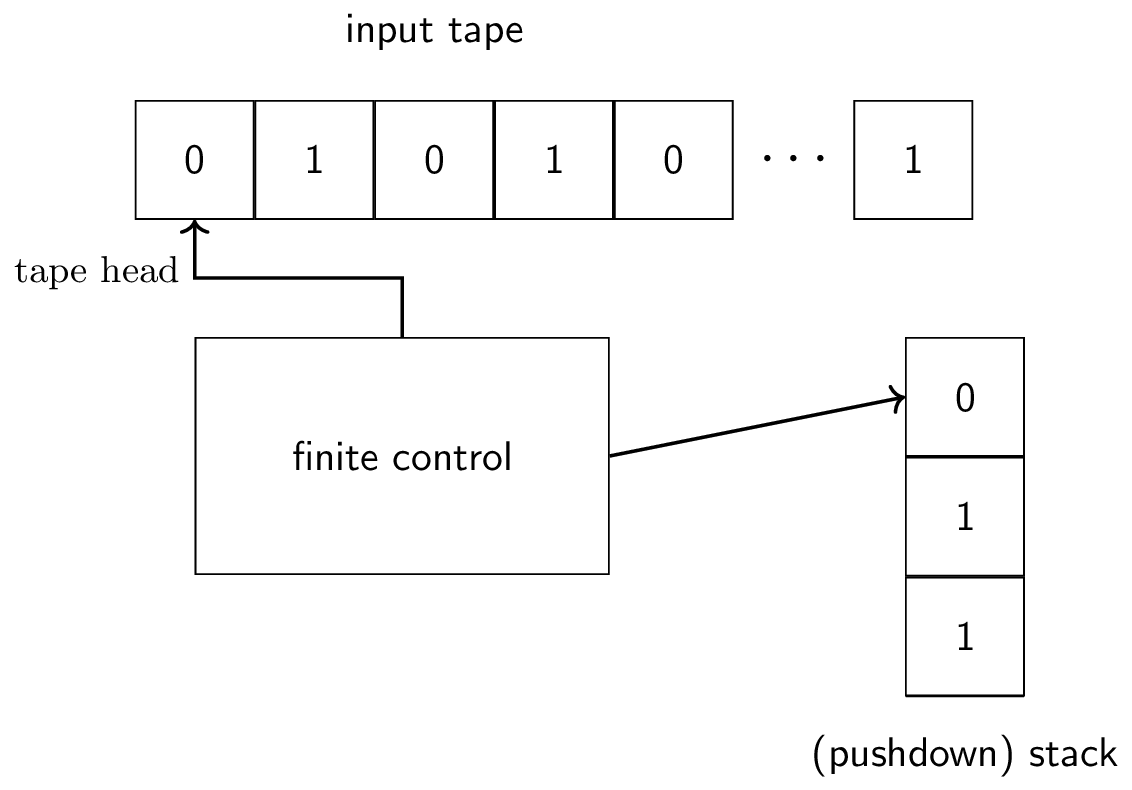

Schematic diagram of a pushdown automata.

A PDA is the same as a FA with a stack. In particular, it has two new

instructions: push <symbol> and pop. Moreover, its If statements

can also depend on the top symbol of the stack. To make it more

explicit, we write If input = <symbol> and stack = <symbol>:.

Technically, we need to push the $ symbol onto the stack at the start to let us check if we have reached the bottom of the stack. However, for simplicity of description, we hide this detail here.

5.3.4Nondeterminism¶

To model nondeterminism, we use a Fork statement, one per

non-deterministic branch. For example, suppose if the next input symbol

is 1, we want to go to Block1 and Block2, then we write:

If input = '1':

Fork:

Move Right

Goto Block1

Fork:

Move Right

Goto Block2

...This is inspired by the notation used in Stanford CS 103 which in turn is inspired by Emil Post’s Formulation 1 and Hao Wang’s Basic Machine B.

These are also called invariants.

This is an induction argument.